Meet the virtual patients training real doctors

By Heather Kelly, CNN, Re-posted by Abdulgafar Abdulrauf Adio (www.econsforumnews.blogspot.com)

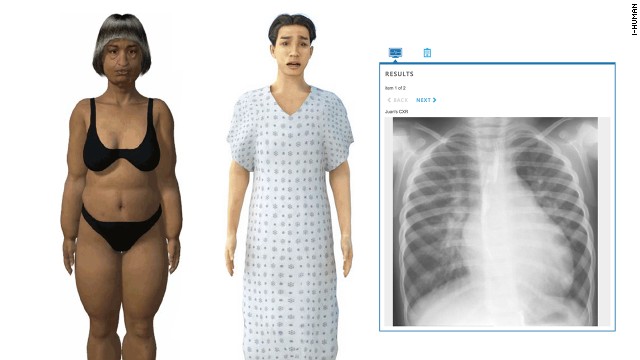

i-Human's interactive virtual patients are used by medical schools to train doctors how to diagnosis illnesses.

i-Human's interactive virtual patients are used by medical schools to train doctors how to diagnosis illnesses.

(CNN) -- Even before the examination begins, it's clear Ann Martinez isn't well.

i-Human's interactive virtual patients are used by medical schools to train doctors how to diagnosis illnesses.

i-Human's interactive virtual patients are used by medical schools to train doctors how to diagnosis illnesses.(CNN) -- Even before the examination begins, it's clear Ann Martinez isn't well.

Her breathing is labored.

You can tell by the raspy sounds and jerky rise and fall of her chest.

Clad in her underwear, she waits quietly for the doctor, letting out the

occasional cough.

The physician starts by

going over her history, asking a few questions and taking her vitals.

Martinez, a smoker with a family history of heart disease, recently had

knee-replacement surgery. She confirms she's having trouble breathing

and complains of some chest pain. While checking her pulse, the doctor

notices that her heartbeat is faster than normal.

On their own, the

symptoms are too common to reach any immediate conclusion. It's possible

she has a simple chest cold, but the signs could indicate something

more dangerous, even fatal. More tests are needed.

There's no risk of

Martinez dying, however, because she isn't real. She is a naturalistic,

interactive virtual patient that lives on a computer screen. The

simulation is part of i-Human Patients, one of a new generation of computer programs used by medical schools to train students and other professionals.

Like a flight simulator

for doctors, i-Human presents cases as complicated, hands-on puzzles

that require real medical skills to figure out. There is minimal

guidance or hand-holding, leaving students to make hundreds of little

decisions and conduct tests as they would when diagnosing a real sick

person.

"A patient shows up in

your office, and that's it. That's real life. You need to start asking

questions," said Norm Wu, CEO of i-Human.

I-Human says its program is an evolution of the popular first-generation virtual patients like InTime's MedU,

which are still used in most medical schools. Those programs and

documents also ask medical students to make a diagnosis but typically

with text, multimedia prompts and multiple choice options.

Medical schools also rely

on a combination of actors and mannequins to help train doctors. Both

have their advantages; working with an actor is great for bedside manner

and interpersonal skills. But they can be expensive, and taking them

home to practice isn't really an option. With a cloud-based computer

program, a medical student can practice his or her diagnoses anywhere

there's Wi-Fi. Data can be collected to let professors know how students

are progressing, highlighting areas where they need improvement.

"If you're a medical

school professor, it's very easy to test for fact-based recall," Wu

said. "How do you tell if somebody has figured out how to appropriately

assess and diagnosis a patient with minimum error?"

Realistic high-tech

training programs like i-Human aren't just another helpful tool. They

have the potential to address a shortage of trained doctors and nurses.

The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services predicts a shortage of more than 20,000 primary care physicians by 2020, driven largely by the aging of baby boomers.

The issue is more severe

in developing countries like India, where there is an average of one

doctor per 1,700 people. In some Indian states the number is closer to 1

per 10,000, and hard-to-reach rural areas

are far worse. Over the next 16 years, India's government wants to

train 1.6 million new physicians. Technology could play a huge role in

the country, where doctors and brick-and-mortar med schools aren't

plentiful.

I-Human is working with

20 educators in India to localize the program, customizing patients and

illnesses for the target market. (It has added an option for more

conservative gowned avatars.)

More accessible

diagnostic training for medical schools could also have an impact on the

misdiagnosis rate. One out of every 20 outpatients is misdiagnosed in

the U.S., according to an April study by BMJ Quality and Safety Journal -- that's 12 million cases a year.

Craig and Anne Knoche

think that more realistic training could dramatically lower that number.

The pair of Silicon Valley veterans launched i-Human with Corey

Cerovsek in 2012 after creating standalone medical simulators for years.

Currently at use in 14

medical schools, the virtual patients are diagnosed as homework, group

projects and tests and as a teaching tool in front of a class. The

program has optional coaching tools like prompts, lessons and quizzes to

keep beginning students on the right track, a common issue when there

are thousands of possible questions to ask and hundreds of labs and

tests to order.

Practicing on an avatar,

no matter how realistic their gout or pneumonia, is obviously not the

same as treating a real human. But a team of graphic artists has worked

to make the avatars mimic real illness as much as possible. The team

designs five or six new "patients" a week.

Each virtual patient has

a name, a medical history, symptoms and an illness. They are a diverse

selection of 3-D illustrations, with realistically rendered bodies,

which makes it possible to see problems like jaundiced skin at a glance.

Audio and animations tip students off to key details, like the sound of

wheezing or the way a patient blinks.

Schools and other third

parties can build their own cases using i-Human and share them with

other customers, similar to selling apps in Apple's App Store. The cases

are peer-reviewed and subject to a review by i-Human's two full-time

staff physicians.

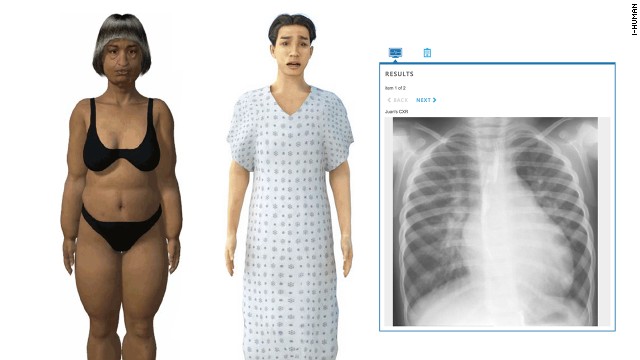

The virtual physical

exams simulates, as much as possible on a screen, the tactical skills

needed for things like measuring blood pressure and testing pupil

reactions. To hear Ann Martinez's heart, the student must know where

exactly to put the stethoscope.

Eventually, if they're

on the right track, Martinez's doctor will order a battery of tests that

include a CT pulmonary angiogram. The result, a black and white image

of real arteries, shows a pulmonary embolism. Pulmonary embolisms are

frequently misdiagnosed and are the third most common cause of death in

hospitalized patients.

If the medical student orders the correct course of treatment, Martinez will live another day and train more future doctors.

0 comments:

Post a Comment